Fort Worth, TX

DOWNLOAD PDFHow Fort Worth, TX, is Using Urban Farming to Improve Healthy Food Access & Economic Development

Fort Worth is a bustling metropolis in Tarrant County, Texas – the fifth largest city in the state and the 16th largest city in the U.S. As with communities across the U.S., many residents in Fort Worth, particularly those in low income areas, have limited access to fresh food.1 These areas of the city are labeled “food deserts,” defined as locations that lack ready access to healthy and affordable food, including vegetables and fruit.2 According to the Tarrant Area Food Bank, an estimated 280,000 Fort Worth residents live in a food desert (situated a mile or more from a full-service grocery store).3 In fact, a recent study found 11 separate zip codes in Tarrant County that are considered food deserts and several zip codes in the City of Fort Worth that do not have a single grocery store in the community.4

Instead of grocery stores, many low-income areas in Fort Worth have multiple fast food chains and convenience stores, neither of which offer fresh produce. Studies have shown that a steady diet of highly processed foods on a long-term basis can result in unhealthy weight-related problems.5 It is thus unsurprising that residents of Fort Worth (along with Dallas and Arlington, Texas) rank in the fourth of five quintiles (i.e., 62.1 percent) in the 2016 Gallup-ShareCare Well-Being Index of Community Rankings for Healthy Eating.6

In addition to limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables, the chair of the Tarrant County Food Policy Council’s Working Group on Community Gardens & Urban Agriculture points out another more fundamental problem: the limited local supply of fresh produce. According to Dave Aftandilian, “If you do a food system analysis that addresses strengths and weaknesses, resources and gaps . . . here in Tarrant County, one of the things that immediately sticks out is – we do not have enough fresh fruits and vegetables being grown locally.” 7 In addition, Aftandilian says, “We have a lot of people who are underutilized in terms of their knowledge and needing a job, needing extra income. We’ve been thinking, how can we use food production as, ideally, a tool for social entrepreneurship . . . to give people a chance to make money, but also to do good for their communities and for Fort Worth and Tarrant County as a whole?”

Fort Worth has many underused and vacant lots in areas that are in need of revitalization and are ideal to convert to food production. Urban farms can provide income, training, and jobs for those who want to grow and sell produce, while at the same time providing locally grown and sourced foods to local businesses, schools, and nonprofit organizations. Yet, although Fort Worth’s current zoning law allows home and community gardens, its provisions did not enable urban farmers to grow and sell produce on-site within city limits.

| Key Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Population: 1 | 854,113 |

| Land Area (in sq. mi): | 339.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity: 2 | 61%-White 18.9%-Black or African American 3.7%-Asian 34.1%-Hispanic/Latino (of any race) |

| Population by Age: 2 | 29.4%-under 18 years 62.4%-18-64 years 8.2%-65 year and older |

| Education: 3 | 80.8%-High school graduate or higher 27.3%-Bachelor’s degree or higher |

| Median Household Income: 3 | $53,214 |

| Population in Poverty: 3 | 18.8% (compared to 17.3% statewide and 15.8% in the U.S. as a whole) |

| Low Income and Low Food Access: 4 | 38.7% of census tracts (138 tracts) |

Given Fort Worth’s need to address food deserts throughout the city, the lack of fresh local produce and healthy food access, the availability of land in the city proper, and the desire of city and community leaders to support healthy food policy initiatives, Tarrant County and Fort Worth decided to collaborate to address these problems.

| Types of Urban Agriculture | Definitions8 |

|---|---|

| Community Garden | A shared garden space for crops or ornamental crops divided up by garden members on land permitted for that purpose. A community garden can be run by a nonprofit, neighborhood association or by a member of the community and is open to the local neighborhood. |

| Urban Farm | A public or private, for-profit or nonprofit agricultural operation consisting of planting and harvesting crops, raising fowl and/or beekeeping. |

| Aquaponics | The combination of aquaculture (farming aquatic species) and hydroponics (plants) to raise crops and fish together. |

THE POLICY DEVELOPMENT PROCESS: The Blue Zones Incentive

Timeline of Events

APRIL 21: Mobile food vending ordinance takes effect

AUGUST 2: Fort Worth City Council adopts urban agriculture amendments to city’s zoning ordinance

AUGUST 18: Forth Worth urban agriculture ordinance takes effect

Back in 2010, the Tarrant Area Food Bank established a program to create and support community gardens and in 2012, partnered with other nonprofit organizations, faculty at local universities, and the Tarrant County Public Health Department to set up a Food Policy Council to address local food access and hunger issues. The Food Policy Council’s mission is to collaborate with all aspects of the County’s food system to advance equitable access to healthy food.

Both Fort Worth and Tarrant County were keenly aware of the need to address food deserts in their communities. In 2013, the Texas Department of State Health Services funded Tarrant County Public Health to perform a local assessment of all zones in the county identified as food deserts and to obtain local data on healthy food availability, cost, and quality for these areas.

In September 2013, Tarrant County released its findings – a Nutrition Environment Assessment Report that encouraged policy and environmental changes to increase the availability of healthy, affordable, and nutritious foods in the designated food deserts. Members of the Tarrant County Food Policy Council and staff at the Fort Worth Planning and Development Department reviewed this report, and began discussing the most effective ways to address the city’s food deserts, such as enabling urban agriculture.

What truly galvanized Fort Worth leaders into implementing health improvement initiatives was the City Council’s 2014 approval of a 5-year project to become a certified Blue Zones® Community.9 The Blue Zones program is a community-led well-being improvement project that encourages communities to adopt healthier lifestyle options.10 One of the many incentives for a community to implement a Blue Zones program is the opportunity to address the physical health of community members as it relates to economic well-being.11 Since employee healthcare is typically a critical business expenses, prospective employers factor the health of a community and its workforce into development decisions.12

Funded by Texas Health Resources, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas, and other major city employers, the Blue Zones Fort Worth project has received strong support from Fort Worth and the City Chamber of Commerce. Civic leaders are investing at least $50 million in private funds to transform Fort Worth into a national model of health and wellness.13 A partnership between founder Dan Buettner and national wellness firm Healthways, Blue Zones projects are in at least 20 cities in California, Iowa, Minnesota, Oregon, and Florida. Fort Worth, however, is the largest U.S. city – and the first in Texas—to implement a Blue Zones project.14

In the words of City Planning Manager Jocelyn Murphy, the Blue Zones initiative provided Fort Worth with the political and civic support, funding, and momentum to help get health improvement initiatives such as the urban agriculture ordinance “over the finish line.” 15

THE POLICY DEVELOPMENT PROCESS: Research and Analysis

Staff from the Fort Worth Planning and Zoning Department began the policy development process by working closely with the Tarrant County Food Policy Council and Blue Zones staff in researching how other communities addressed food deserts across the U.S. The Council set up a Steering Committee to review best practices for community gardens and urban agriculture in major cities. Committee members looked closely, for example, at zoning language and policies for urban farms/agriculture and community gardens in Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Jersey City, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Nashville, New York City, Philadelphia, Portland, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington D.C. During this process, they also looked at incentives that cities used to encourage urban agriculture, and other options such as rooftop gardening (ill-suited for Fort Worth’s climate).

As a result of this process, staff prepared a detailed matrix of best urban farming practices from all communities. The group – including City Planner Jocelyn Murphy, Blue Zones staff and experts in water management and land use – compared and analyzed all options to determine the urban agriculture model that would work best for the City of Fort Worth. After many meetings, the City’s Planning and Zoning Department prepared a preliminary draft of an ordinance that allowed urban agriculture throughout Fort Worth, with development standards and uses as appropriate in different zoning districts.

THE POLICY DEVELOPMENT PROCESS: Collaboration and Community Input

To ensure that the ordinance was tailored as closely as possible to fit the disparate needs of Fort Worth residents who lacked access to healthy foods, members of the work group did broad outreach to many different stakeholders in the city. For more than a year – both before and after the ordinance was initially drafted – the working group met with community gardeners, master gardeners, local nonprofits, academics, aquaponics experts, members of the metro beekeepers’ association, and others, to solicit input on the proposed ordinance. Group members reached out to anyone they knew in the area who had an interest in farming. In addition, the group consulted with public health and food justice experts at Texas Christian University, the University of North Texas, and the Texas AgriLife Extension and members of the American Community Garden Association.

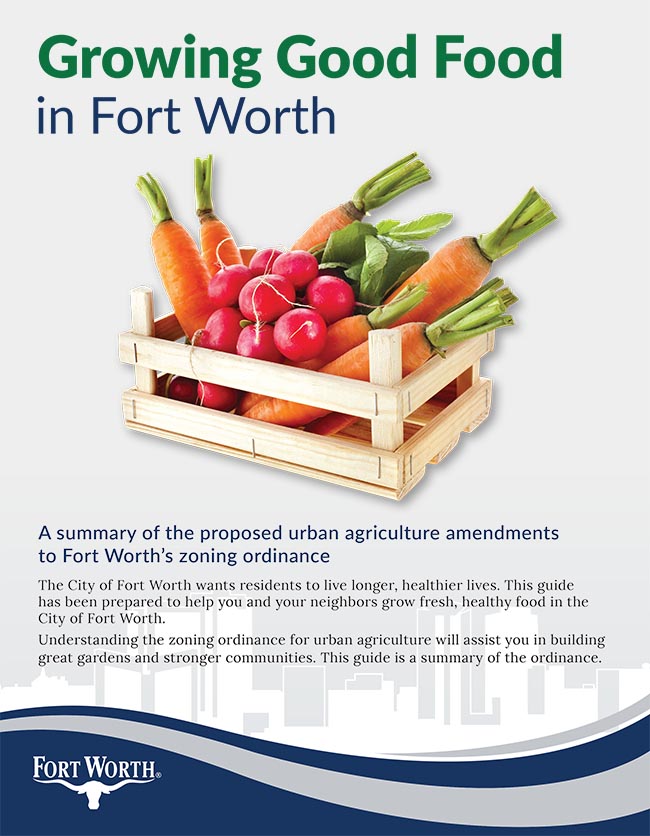

The working group also broadly distributed a brief handout developed by city staff that explained the ordinance using simple non-legal language and colorful graphics.16 Moreover, the city disseminated policy news and information, along with the latest ordinance drafts and amendments through email and via Nextdoor, a popular private social network for neighborhoods, accessed by a large number of registered neighborhood associations throughout Fort Worth.17

THE POLICY DEVELOPMENT PROCESS: Final Adoption

On Aug. 2, 2016, as the ordinance was being finalized, the Fort Worth City Council held a public meeting that drew a large number of attendees. Several supporters testified on behalf of the policy. Due to thoughtful planning on the part of proponents, the proposed ordinance encountered no opposition.

Following public testimony, the City Council voted to approve language amending the city’s zoning ordinance to allow urban farms, aquaponics inside a covered structure, and sales of produce grown in all zoning districts in the city. Each zoning district (i.e., residential, commercial and industrial) is allowed different sales and production uses, with residential areas more restricted to ensure that residents are not disrupted by urban agriculture activities. The city requires that urban farmers (depending on lot size and type) provide various documentation, such as a site plan, a Land Use Certificate of Occupancy, and a Development Permit. Farmers must also pay water, sewer, and storm water fees.

Anticipated Policy Impact

On August 18, 2016 – only two weeks after adoption – Fort Worth’s urban agriculture policy took effect. Because policy implementation is so recent, the ordinance’s impact is not yet known. According to Dave Aftandilian, assessing the urban agriculture policy’s impact on the community will be “a decades-long process.” Some farms will remain and grow and become successful, while others may be temporary or experimental. The dream, says Aftandilian, is “to make it possible for more people to grow healthy food in their communities, and ideally, be able to make some extra money selling that produce right in their community. And if they scale it up a little bit, maybe at one of the local farmers’ markets.”

Aflandilian describes a local developer who recently contacted the Food Policy Council. The developer was interested in building affordable apartments in a Fort Worth neighborhood that was part low-income and part middle-income. He owned a plot of undeveloped land in the area and, because he had recently learned of the urban agriculture ordinance, he was looking for an urban farmer to farm the land and sell the produce on site. This developer, says Aftandilian, “is already using the ordinance exactly how we hoped people would . . . which is to see it as a framework to sell and grow healthy food in low-income communities.” This is just one way the urban agriculture ordinance is also designed to impact health equity, by providing fresh food to underserved communities and by enabling members of these communities to produce and market local food as a tool for social and economic development.

Lessons Learned

Some key lessons and best-practices were shared by the experts we spoke with for this case study. These lessons include the following:

-

- Engage people, solicit feedback from experts, and invite input from all affected communities as soon as feasible in the policy planning process. Meet with people in person, if at all possible, and draw on the experiences of those with backgrounds in relevant areas such as farming, gardening, land use, and public health.

-

- Anticipate opposition, listen to concerns, and be willing to compromise if possible. Some Fort Worth residents, for example (including many members of a beekeepers’ association), had misgivings about government regulation on principle, as well as misunderstandings about the city’s regulatory authority to pass such an ordinance. Despite their initial opposition to the ordinance, once they were able to meet with ordinance proponents, ask questions in public meetings, and see several of their concerns acknowledged and addressed in revised drafts, many became supportive of the policy.

-

- Political support and broad outreach beyond public health can significantly advance healthy food policy change. In this instance, the mayor’s endorsement of the Blue Zones project and Blue Zone’s collaboration in the process helped raise the profile of healthy foods initiatives in general and resulted in ordinance support by government and civic leaders, food system stakeholders, and business representatives, as well as local residents and the public health and social services communities.

-

- Urban agriculture is in the public interest and can accomplish multiple goals in addition to improving resident health. For instance, it can vitalize neighborhoods, encourage entrepreneurship, support economic development, and provide job opportunities and training for members of underserved communities.

One note: on April 21, 2016, the City Council approved an amendment to the city’s zoning ordinance to allow fresh market mobile vending and a mobile vending vehicle on private property in residentially zoned districts.18 Both the mobile vendor and the urban agriculture ordinances are ways in which Fort Worth is tackling limited healthy food access in ways that enhance the neighborhood and surrounding environment and encourage resident collaboration and economic well-being.

About the Healthy Food Policy Project (HFPP)

The HFPP identifies and elevates local laws that seek to promote access to healthy food while also contributing to strong local economies, an improved environment, and health equity, with a focus on socially disadvantaged and marginalized groups. HFPP is a multiyear collaboration of the Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law School, the Public Health Law Center, and the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity at the University of Connecticut. This project is funded by the National Agricultural Library, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Additional Acknowledgements

This case study relies heavily on information provided during interviews and subsequent communications with Jocelyn Murphy, Planning Manager, Zoning and Land Use, City of Fort Worth (Aug. 23, 2017) and Dave Aftandilian, Texas Christian University Associate Professor of Anthropology and chair of the Tarrant County Food Policy Council Chair’s Working Group on Community Gardens & Urban Agriculture (Sept. 12, 2017). The Healthy Food Policy Project (HFPP) collaborators thank these individuals for their contributions. We have not included citations to the information they have contributed throughout the body of this case study, but have relied upon it unless another source is indicated. Photos are included courtesy of City of Fort Worth, Texas, and Tarrant Area Food Bank’s Learning Garden at Ridglea Christian Church in Fort Worth.

The HFPP also thanks its Advisory Committee members for their guidance and feedback throughout the project. Advisory Committee members are: Dr. David Procter with the Rural Grocery Initiative at Kansas State University, Dr. Samina Raja with Growing Food Connections at the University of Buffalo, and Kathryn Lynch Underwood with the Detroit City Planning Commission. Previous advisory committee members include Pakou Hang with the Hmong American Farmers Association and Emily Broad Leib with the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic. Renee Gross, JD, served as a project consultant from 2015-2018.

Notes

1 Telephone interview with Dave Aftandilian, Texas Christian University Associate Professor of Anthropology and chair of the Tarrant County Food Policy Council’s Working Group on Community Gardens & Urban Agriculture (Sept. 12, 2017).

2 See Tarrant County Public Health, Tarrant County Food Desert Project: Nutrition Environment Assessment Report (Sept. 30, 2013), http://access.tarrantcounty.com/content/dam/main/public-health/12-19-2013FOOD_DESERT_final_report.pdf.

3 Edward Brown, Food Deserts: A Coalition Works Toward Bringing Fresh Food to Poor Parts of Town, Fort Worth Weekly (Dec. 16, 2015), https://www.fwweekly.com/2015/12/16/food-deserts.

4 See Abby Block, The Face of Hunger in North Texas, the109.org (Oct. 11, 2017), http://the109.org/2017/10/11/the-face-of-hunger-in-north-texas; see also Tarrant County Public Health, Tarrant County Food Desert Project: Nutrition Environment Assessment Report (Sept. 30, 2013), http://access.tarrantcounty.com/content/dam/main/public-health/12-19-2013FOOD_DESERT_final_report.pdf.

5 Atil Arnarson, Why Processed Meat is Bad for You, HealthLine (2017), https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/why-processed-meat-is-bad#section9; Kris Gunnars, Nine Ways that Processed Foods are Harming People, Medical News Today (2017), https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318630.php.

6 Gallup-Sharecare – Well-Being Index, State of American Well-Being: 2016 Community Rankings for Healthy Eating (2015/2016) (a ranking of communities whose residents ate healthy all day the previous day), http://www.well-beingindex.com/2016-community-rankings.

7 Dave Aftandilian, supra note 1.

8 Fort Worth, Growing Good Food in Fort Worth: A Summary of the Proposed Urban Agriculture Amendments to Fort Worth’s Zoning Ordinance (last accessed Oct. 20, 2017), http://fortworthtexas.gov/files/Urban%20Ag%20draft%20final%207.7.2016.pdf.

9 Healthways, Blue Zones Project by Healthways website (last accessed Oct. 30, 2017), http://www.healthways.com/bluezonesproject.

10 Fort Worth Chamber, Improving Well-Being in Fort Worth (last accessed Oct. 20, 2017), https://info.bluezonesproject.com/fort-worth-chamber-of-commerce-makes-well-being-its-business.

11 Sarah Bahari, Blue Zones Project Off and Running in Fort Worth, Star-Telegram (Nov. 28, 2015), http://www.star-telegram.com/news/local/community/fort-worth/article47027470.html.

12 Terry Clark et al., Amenities Drive Urban Growth, 24 J. Urban Affairs 5, 493-515 (2002).

13 Id.

14 Id.

15 Telephone interview with Jocelyn Murphy, Planning Manager, Zoning and Land Use Section, City of Forth Worth Planning and Development Department (Aug. 23, 2017).

16 Fort Worth, Growing Good Food in Fort Worth, supra note 8.

17 Nextdoor, https://nextdoor.com/login (last accessed Oct. 20, 2017

18 City of Fort Worth, Ordinance No. 22154-04-2016 (April 21, 2016), http://publicdocuments.fortworthtexas.gov/CSODOCS/0/doc/119737/Page1.aspx.

19 See Tarrant County Food Policy Council website, http://tarrantcountyfoodpolicycouncil.org/?reqp=1&reqr=nzcdYaEvLaE5pv5jLab=.

Key Demographics Table Notes

1 Source: Vintage 2016 Population Estimates: Population Estimates

2 Source: 2010 U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts

3 Source: 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Profiles

4 Source: 2015 USDA/ERS Food Access Data