Boston’s Good Food Purchasing Policy, Part 2:

DOWNLOAD PDFAssessing the implementation of the city’s values-based procurement requirement

The passage of the GFPS in Boston resulted from an initiative driven by a diverse coalition of stakeholders committed to values-based food procurement.3 Now Mayor, then Councilor-at-Large, Michelle Wu introduced the ordinance.4 Supporters of Boston's GFPS initiative hoped to leverage city purchasing power to improve sustainability, fair working conditions, and local opportunity in the regional food system. At the time, Boston joined nine other cities that passed laws or municipal ordinances based on templates provided by the Center for Good Food Purchasing. The Center for Good Food Purchasing continues to support Boston and Boston Public Schools (BPS) in the implementation of values-based procurement policies, which includes supporting Boston with action planning and program updates released in 2023.

To date, implementation of the GFPS has primarily focused on procurement at Boston Public Schools (BPS), the city's largest food purchaser. Since 2019, BPS has increased the number of values-aligned products it purchases by reaching out to suppliers, hiring a new director with Good Food Purchasing Program (GFPP) expertise, and changing bidding practices to incorporate GFPS values.

The Healthy Food Policy Project (HFPP) produced a case study that followed the policy development, coalition building, and passage of ordinance §4-9. This updated case study highlights Boston's progress toward implementing the values-based procurement required by the GFPS and provides a few key lessons learned.

The Healthy Food Policy Project (HFPP) produced a case study that followed the policy development, coalition building, and passage of ordinance §4-9. This updated case study highlights Boston's progress toward implementing the values-based procurement required by the GFPS and provides a few key lessons learned.

The Center for Good Food Purchasing released an updated version of the Good Food Purchasing Program framework, the Good Food Purchasing Standards 3.0 in August of 2023. The comprehensive update centers the government food system values around the principals of equity, accountability, and transparency:

- Local and Community-Based Economics

- Environmental Sustainability

- Valued Workforce

- Animal Welfare

- Community Health and Nutrition

Food Procurement at Boston Public Schools

Food procured by BPS must first meet the requirements of state and federal law. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) is a federal law that funds school districts to provide free and discounted lunches to students.6 BPS also participates in the Community Eligibility Provision of the NSLP, which allows all meals to be provided at no cost to all students.7 As a condition of receiving federal funds, schools must abide by NSLP nutrition and meal composition standards.8 BPS must ensure the meals it serves meet these requirements before evaluating purchases based on the GFPS. Consequently, compliance with those requirements is a threshold consideration.

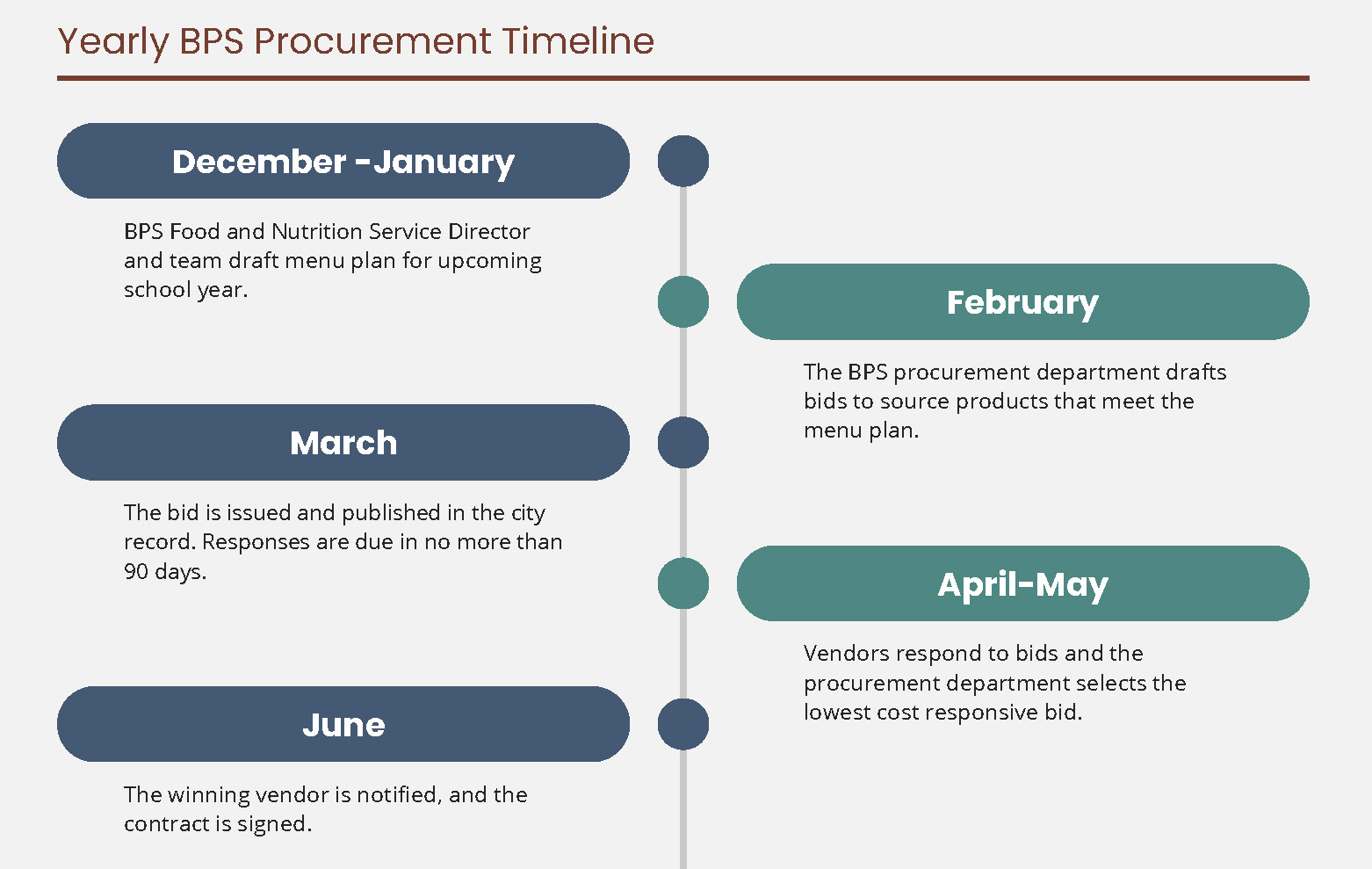

Bidding

Local government entities, including schools, purchase goods and services primarily through formal bidding. Bidding generally refers to the process by which government entities create a written request for a product or service and then solicit vendors to submit quotes.11 In the context of food procurement, this generally includes documents that list price, quantity, quality, and delivery requirements. As required by the City of Boston’s procurement system, bidding with BPS also requires vendors to complete background checks, safety certifications, fair wage declarations, and truck safety guidelines. BPS issues multiple separate bids for different food products, such as fresh produce, pizza, beef products, or seafood.

For a school system as large as BPS, the volume and delivery requirements make fulfilling each bid complex. The winning bidder for the fresh produce bid in 2023 was FreshPoint, a division of Sysco. FreshPoint’s winning bid contained price and quantity quotes for 96 separate products totaling over three million dollars.12

The Baseline Assessment for Boston Public Schools

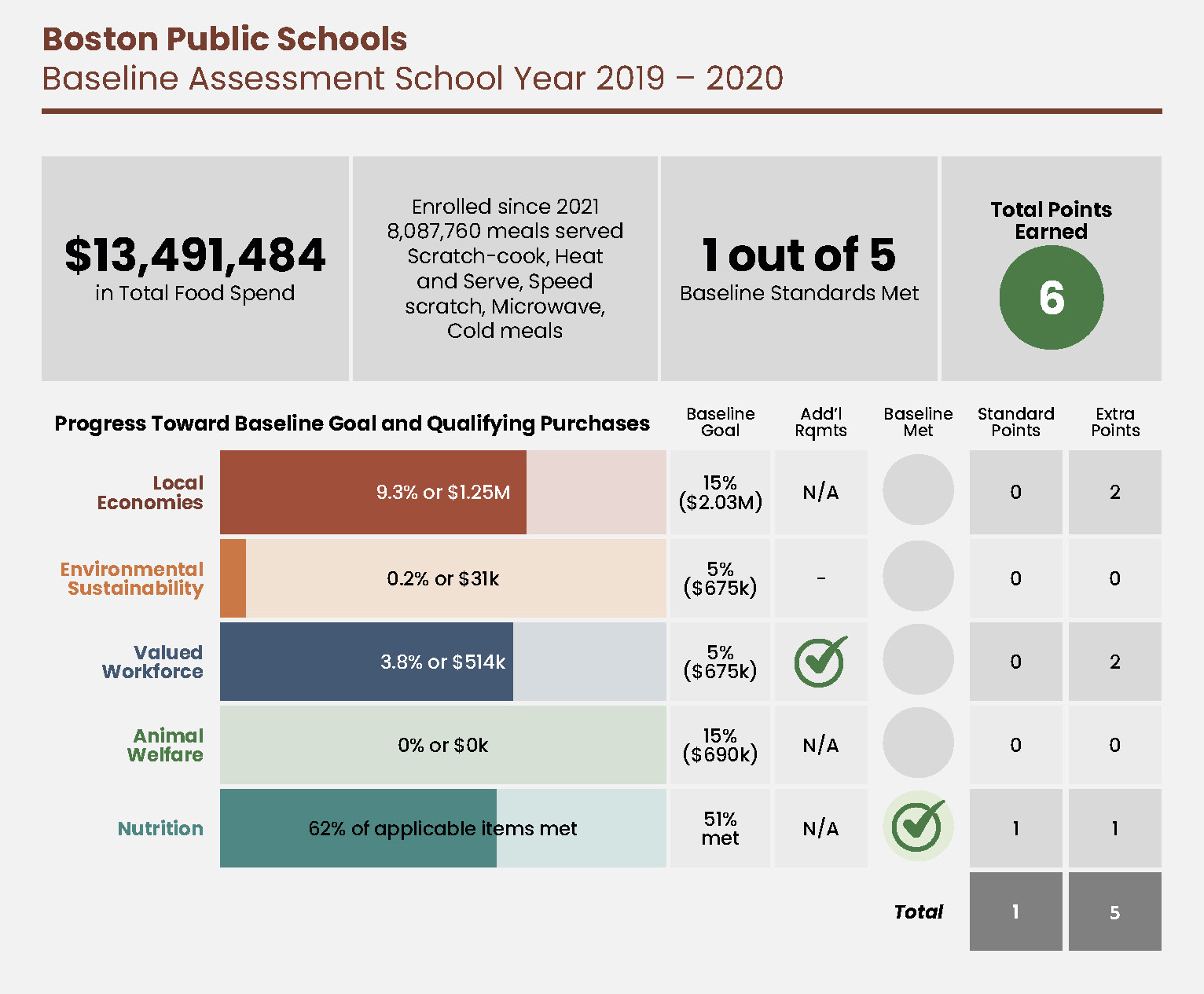

GFPP scores products based on five qualifying criteria that range from level 1 to level 3. The criteria consist primarily of geographic information or third-party production certifications. The chart above from the BPS Baseline Assessment shows each value category with the corresponding initial goal and BPS score displayed as a percentage of overall spending. Due to limited data and other pandemic related factors, BPS could only demonstrate qualifying purchases sufficient to reach its initial goal in the nutrition category. A companion document, released with the assessment, details the qualifying criteria for each category.

In the case of the local economies category, the criteria define qualifying products as those grown or processed in the six states of New England.16 Unlike other local definitions, the GFPS does not include a mileage radius for local products but rather is focused on purchasing from New England as reflective of a regional food system. This difference from the GFPP Standards in other regions was decided by a local committee of food system advocates that sought to ensure that GFPP supported existing local and regional efforts, such as New England Feeding New England.17 The size of the source farm is also considered, as products are rated from level 1 (very large farms) to level 3 (medium) by farm revenue.18 During the 2019-2020 school year, 9.3% of products sourced by BPS satisfied these qualifying criteria because they were sourced from New England. Local economies qualifying products included bakery items from Calise & Sons Bakery in Lincoln, Rhode Island, and seed butter from 88 Acres in Canton, Massachusetts. Both companies were qualified as very large companies and scored at level 1.19

Local Economies Baseline Requirement

| Qualifying Criteria | Extra Points |

|---|---|

Distance of source farm from institution

|

|

The other criteria consist of third-party certifications of production practices that are commonly found on consumer products. In the environmental sustainability category, for example, Level 1 qualifying criteria include certifications such as Sustainably Grown Certified,20 while level 3 can be met by sourcing USDA Organic products. BPS demonstrated fewer qualifying purchases in this category than in local economies. The baseline assessment showed $31,000 of spending in this category (0.2% of total food spend), of which USDA Organic 88 Acres products accounted for 65%.

Environmental Sustainability Baseline Requirement

- Purchasing 15% of products that are third-party certified sustainable at any Level or 5% of product at Level 3

- Reducing carbon and water footprint of animal product purchases by 4% from the first year of participation AND auditing food waste to implement food waste reduction strategies

| Qualifying Criteria | Extra Points |

|---|---|

|

|

| Additional Baseline Requirements |

|---|

|

Good Food Purchasing Standards Policy Implementation

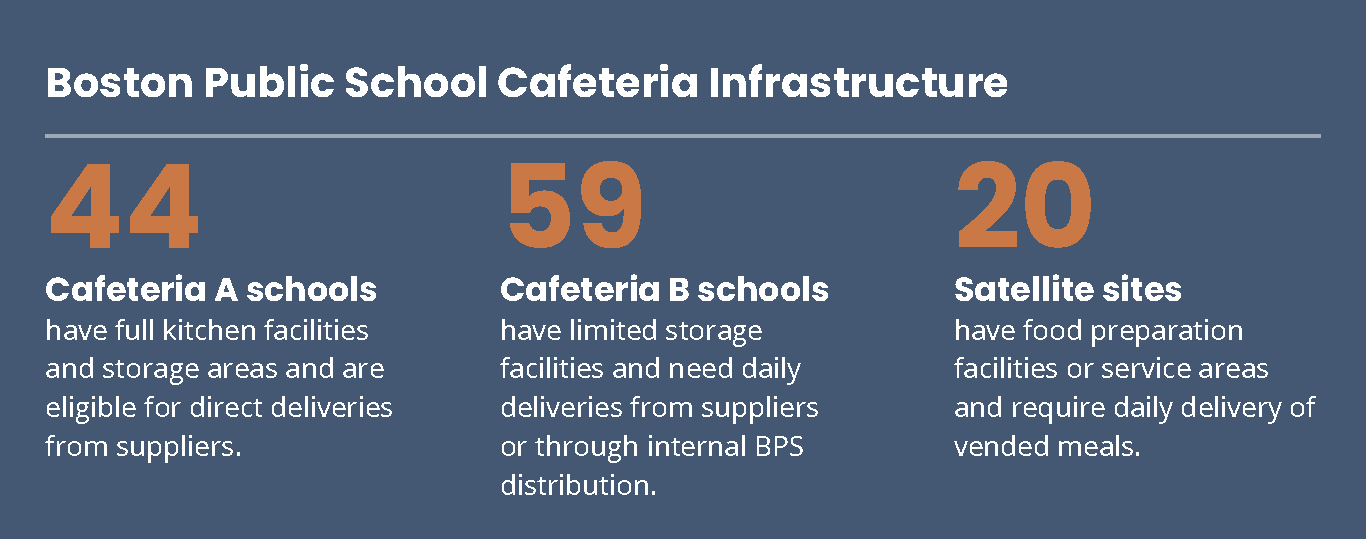

GFPS implementation also coincides with substantial investment in cafeteria infrastructure to improve fresh food options. Over the last five years, BPS has renovated or improved nearly all cafeterias across the city. As of 2023, 119 of 125 schools now have the facilities to cook food on site, compared to approximately 40 schools in 2018.21 This improved food service capacity has created more opportunities for product procurement that meets GFPS goals, rather than relying on premade heat and serve lunches.22

1. New Food Service Leadership

2. Bidding Changes

Boston Public Schools achieved this increase in two ways. First, BPS added criteria to its fresh produce bidding, which requested a specific quantity of New England grown produce in 2023.23 This language change resulted in an increase of over $350,000 of locally grown produce available to BPS compared to 2022 when they requested produce without indicating a geographic preference. The existing produce vendor, Fresh Point, was able to meet these geographic criteria.

Second, Boston Public Schools issued a standalone New England grown frozen produce bid in 2023 that included the option for vendors to bid on individual products, or line items.24 In prior years, BPS sought its entire requirement of frozen vegetables from one vendor. The 2023 frozen produce bid instead treated each product as an individual bid open to different vendors. This change in the bidding procedure allowed Harvesting Good, a public benefit corporation started by the Good Shepherd Food Bank in Maine, to win the bid for frozen broccoli. Harvesting Good is a vendor whose mission is “to improve access to nutritious food for all consumers and strengthen regional food systems by creating a mid-scale food processing venture,” which specifically aligns with GPFS values.25 Currently, Harvesting Good focuses only on processing and freezing locally grown broccoli for wholesale. The change to line-item bidding allowed them to win the bid for broccoli, without having to source the other requested products. Harvesting Good supplied over 34,000 pounds of frozen broccoli to be served in BPS cafeterias for the 2023-2024 school year.26

3. Vendor Outreach

BPS has already made important progress collaborating with suppliers to improve procurement and record keeping. Section 4-9.2(1) of the GFPS requires city departments to notify vendors about the GFPS values and require they provide sourcing data for scoring.27 First, BPS successfully included GFPS values language in its Invitations for Bid which requires vendors to provide sourcing information.28 Invitations for Bid now contain language requiring the vendor “to share data that will help FNS complete an assessment of food procurement practices that will help us better understand the extent to which the food we are purchasing aligns with GFPP’s values…”29 Information requested includes sourcing information as well as detailed information on pack sizes, quantity, and item weights.

Nancy Fisher, a consultant working with Boston Public Schools on GFPP implementation, noted that vendors have embraced these measures showing little resistance to increased record keeping. BPS has been successful at encouraging vendors with similar values to participate in bidding. Harvesting Good, for example, was approached by BPS consultants about bidding opportunities. They would not have been aware of the opportunity with BPS absent this outreach. Nancy Fisher also hosted a gathering of farmers and food vendors to discuss how to improve collaboration and streamline the procurement process with the goal of increasing the number of vendors who participate in bidding.30

The Office of Food Justice plans to focus on helping small and BIPOC-owned vendors to better understand how to successfully bid on contracts with BPS and other city agencies. This includes working with other city and state offices to break down the procurement processes and forms required, as well as supporting small and BIPOC-owned food businesses to become aware of and part of the city’s Certified Business Directory. Finally, the Office of Supplier Diversity has created new levers to support Minority and Women Owned Enterprises (MWBE) vendors to win contracts, like the City’s new Inclusive Quote Contract law, which raises the threshold requiring written quotes to $250,000 for MWBE vendors.

4. Improved Collaboration and Stakeholder Engagement

In addition, OFJ has been working with the Mayor’s Office, the Boston Good Food Purchasing Coalition, and youth engagement partners to identify meaningful opportunities for food system advocates and community members (such as students or families participating in BPS school meals) to form a Community Advisory Council as required by §4-9.4. OFJ is conducting ongoing research to develop this Advisory Council to increase transparency and involve community members in procurement decisions, while providing meaningful opportunities for input. However, the number of steps and tight timelines in the procurement process, as well as state ethics laws regarding public meetings, make developing compensated advisory bodies in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts complex. OFJ is working to ensure that transparency in procurement processes is a cornerstone of the ordinance’s implementation.

Finally, the City of Boston does not have jurisdiction over many of the large public food purchasers located within the city, such as airports, convention centers, hospitals, and jails. OFJ is working with the Green Ribbon Commission Climate Justice Network to bring these institutions and other large food purchasers within the City of Boston together to develop shared values-based purchasing efforts beginning in 2024. Aliza Wasserman, Director of the Office of Food Justice since 2022, hopes that by supporting large public and private agencies to work together, the city will strengthen values-based supply chains for Boston throughout the Northeast, through strategies like developing unified metrics, understanding market development needs, and sharing best practices for vendor outreach.

Next Steps and Future Planning

BPS Food Service Goals

- Central scratch cooking

- Upgrade all cafeterias

- Improve kitchen staff capacity and instituting best practices

- Improve student input

- Incorporate food education

- Daily self-serve salad bars

The BPS Food and Nutrition Service also hopes to improve outreach to new vendors and encourage increased participation. Even prior to the GFPS, BPS rarely received more than two bids for its larger procurement requests. Tanner indicated that the procurement team hosted technical assistance events for vendors beginning in 2023 to explain the bidding process and help them understand paperwork requirements. The documentation required can present a hurdle for smaller companies with less experience with formal bidding. Providing technical support could increase the number of suppliers who respond to BPS food bids. Technical assistance could also help meet the equity value contained within Boston’s version of the GFPS.33 Finally, reducing administrative burdens in bidding could help increase the participation of disadvantaged and minority communities.

Challenges to GFPS Value-Based Procurement

The reimbursement rate per meal provided by the National School Lunch Program limits the ability of BPS to spend more on values-aligned products. GFPS products must be price competitive with their conventional counterparts to meet budgetary requirements in most circumstances.

Lowest Cost Bidding

Massachusetts Ch. 30B requires the lowest cost bidding procedures for most food purchased by BPS. In most circumstances, BPS cannot select a vendor that supplies GFPS aligned products over a lower priced competitor. Allowing GFPS values to be considered in bid awards can be done by writing bids that request values-aligned products specifically.

Burdensome Scoring Certifications

Scoring for the GFPS relies primarily on third-party certifications. These certifications can be expensive or burdensome to vendors, and many do not certify their products. Harvesting Good does not have production certifications to demonstrate its use of sustainable farming practices. The certification requirements in the GFPS can fail to credit BPS with sourcing values-aligned products.

Equity and Access for Smaller Vendors

Many vendors not currently working with the city note that the process for submitting a bid is labor-intensive, complex, and confusing. Bid responses require substantial paperwork and bids are often due in as little as thirty days. The limited support provided to new vendors privileges larger, established food service companies.

Limited Number of Suppliers

In many cases, BPS has a limited choice of vendors due to transportation and storage needs for its large number of schools. Prior to the GFPS, the complexity of selling to BPS sometimes limited the number of companies responding to a single vendor. Adding additional requirements such as the GFPS could further limit the number of vendors who respond to bids by adding additional requirements.

Lessons Learned

For this case study, we spoke with school food procurement professionals who shared the following suggestions:

1. Ensure leadership and financial commitment.

Organizational commitment, both personal and financial, is essential to prioritizing values over traditional procurement practices. Leadership commitment to GFPS goals is a decisive factor in program success. Financial commitment is also needed to improve cafeteria facilities and fund additional staff work on GFPS implementation.

2. Collaborate with existing suppliers.

The most cost-effective way to improve qualifying purchases is to work with existing vendors. Boston Public Schools’ experience shows that many vendors are willing to source different products or are actively interested in the GFPS. Existing vendors may also act as distribution networks for smaller producers.

3. Be creative with bids.

Bid drafting plays an important role in which vendors can respond and fill orders. The first step to purchasing more values-aligned products is drafting bids that ask for those products. Changing to line-item bidding or adding values-based preferences can help make bids accessible to smaller companies or vendors.

4. Plan for future improvement.

Changing procurement practices takes time and having a multi-year plan gives structure and benchmarks to the process. Other cities considering the GFPP should anticipate an implementation process that takes multiple years.

5. Seek out expertise.

Consultants who understand the regional food supply chain provide important expertise that can help procurement staff implement GFPS more quickly. Outreach to vendors conducted by BPS consultants was an important factor in finding vendors that shared GFPS values.

Trends to Watch in Local Food Procurement

First, the Center for Good Food Purchasing released an updated version of the Good Food Purchasing Program framework, the Good Food Purchasing Standards 3.0 in August 2023. The comprehensive update centers the five food system values around the principals of equity, accountability, and transparency. The updated program also gives credit to schools that make improvements to their internal processes and makes it easier to receive credit for purchasing local food. According to the Center for Good Food Purchasing, all institutions participating in GFPP will receive future assessments under this rubric, complemented by an action plan co-developed with institutional leaders to advance their Good Food Purchasing progress across each value category.

Second, effective July 1, 2024, USDA now allows schools participating in the NSLP to request “locally grown, raised or caught” produce or minimally processed food in procurement requests.34 Prior to this rule change, locality was only allowed as a scoring criterion, not a bid requirement. School procurement departments are also given the freedom to define local for their area.35 Previously to this rule change, only regional preferences were allowed, as used by Boston Public Schools in its bidding request.36 Boston could, following this rule change, issue bids requesting only Massachusetts grown produce if desired. This change will likely have a greater impact in large states or areas that do not already draw on regional food systems.

Acknowledgements

CAFS thanks the following people for reviewing this case study and providing edits and feedback: staff from the Boston Public Schools Food and Nutrition Services, including Anneleise Tanner, Executive Director, and Nancy Fisher, Special Projects; River Figueroa, Procurement and Contracts Manager for Boston Public Schools; staff from the Boston Mayor’s Office of Food Justice, including Aliza Wasserman, Director, and Laura Alves, Manager of Strategic Initiatives; staff from the Center for Good Food Purchasing including Lauren Taniguchi, Communications Manager, and Molly Riordan, Director of Institutional Impact; and Matt Chin, President of Harvesting Good. Reviewers did not review the final document and do not necessarily agree with all statements in the case study, but they provided tremendously thoughtful guidance and feedback on its content.

Endnotes

2 Boston, Mass., Code Chapter IV, § 4-9 (2019). https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/boston/latest/boston_ma/0-0-0-17851

3 Healthy Food Policy Project, Boston Case Study. https://healthyfoodpolicyproject.org/case-studies/boston-ma. (Sept. 21, 2020).

4 Healthy Food Policy Project, Boston Case Study. https://healthyfoodpolicyproject.org/case-studies/boston-ma. (Sept. 21, 2020).

5 Boston Public Schools: School Listings 2023-2024 (last visited 9/25/23). https://www.bostonpublicschools.org/domain/175

6 42 U.S.C. §1751 et seq., see also, Kara Clifford Billings, School Meals and Other Child Nutrition Programs: Background and Funding Congressional Research Service (Updated May 23, 2023). https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46234

7 88 FR 65778. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/09/26/2023-20294/child-nutrition-programs-community-ligibility-provision-increasing-options-for-schools#footnote-4-p65779

8 87 FR 6984, February 7, 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/02/07/2022-02327/childnutrition-programs-transitional-standards-for-milkwhole-grains-and-sodium

9 M.G.L. Ch. 30B §5(a). https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleIII/Chapter30B/Section5

10 M.G.L. Ch. 30B §5(a). https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleIII/Chapter30B/Section5

11 The Chapter 30B Manuel: Procuring Supplies, Services and Real Property, 9th Edition, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Office of the Inspector General (May 2023). https://www.mass.gov/doc/the-chapter-30b-manual-procuring-supplies-services-and-real-property-legal-requirements-recommended-practices-and-sources-of-assistance-9th-edition/download

12 Invitation for Bid: Fresh Produce to Boston Public Schools, Price Quote Worksheet. #EV00011979

13 Boston Public Schools, Baseline Assessment, School Year 2019-2020. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IleF4k51Zk0wCmuNY4DxqgTY3xJ5vXWq/view

14 Boston Public Schools, Companion Document to Baseline Assessment, (January 20, 2023). https://www.boston.gov/departments/food-justice/good-food-purchasing-program/good-food-purchasing-program-boston-public-schools

15 Boston Public Schools, Baseline Assessment, School Year 2019-2020 (January 20, 2023) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IleF4k51Zk0wCmuNY4DxqgTY3xJ5vXWq/view?usp=sharing

16 Boston Public Schools, Companion Document to Baseline Assessment, (January 20, 2023). https://www.boston.gov/departments/food-justice/good-food-purchasing-program/good-food-purchasing-program-boston-public-schools

17 New England Feeding New England: Cultivating a Reliable Food Supply, N. England Food Sys., https://nefoodsystemplanners.org/ (last visited Nov. 8, 2024).

18 Boston Public Schools, Companion Document to Baseline Assessment, (January 20, 2023). https://www.boston.gov/departments/food-justice/good-food-purchasing-program/good-food-purchasing-program-boston-public-schools

19 Boston Public Schools, Baseline Assessment, School Year 2019-2020 (January 20, 2023) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IleF4k51Zk0wCmuNY4DxqgTY3xJ5vXWq/view?usp=sharing.

20 SCS Global Services, Sustainably Grown Certification. Certification Standard for Sustainably Grown Agricultural Crops (December, 2022). https://cdn.scsglobalservices.com/files/program_documents/SCS%20Standard_SG%20001_FS_V3.0%20%282022%29.pdf

21 Boston Public Schools at a Glance, BPS Communications Department, Revised January 2018. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ZpXLcQxLiFazFZD7zvkiS8RB4Ppc54UU

22 Boston Public Schools, Presentation to the City Council FY23. May 3, 2022. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ExiLHBMraYKmo071KRFfgCFLpxsD28OT/view

23 Invitation for Bid: Fresh Produce Delivered to Dorchester Central Kitchen Through June, 2020, Price Quote Worksheet, #EV00009970.

24 Invitation for Bid: New England Grown Frozen Produce, Price Quote Worksheet, #EV00012071.

25 Harvesting Good, About Us. https://www.gsfb.org/about-us/harvesting-good/#:~:text=Harvesting%20Good%20is%20a%20for,mid%2Dscale%20food%20processing%20venture.

26 Contract: BPS and Harvesting Good: New England Grown Produce for Boston Public Schools, Directly to Central Kitchen. Contracting ID# 58552 (July 1, 2023).

27 Boston, Mass., Code Chapter IV, § 4-9.2(1) (2019). https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/boston/latest/boston_ma/0-0-0-17851

28 Kara Clifford Billings, School Meals and Other Child Nutrition Programs: Background and Funding Congressional Research Service (Updated May 23, 2023). https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46234

29 Invitation for Bid: Fresh Whole, Processed and Portioned Produce Delivered to Schools, Price Quote Worksheet, EV#00010841

30 Anneliese Tanner & Nancy Fisher, personal interview, August 17, 2023

31 Anneliese Tanner & Nancy Fisher, personal interview, August 17, 2023

32 Invitation for Bid: Fresh Produce to Boston Public Schools, Price Quote Worksheet. #EV00011979

33 Boston, Mass., Code Chapter IV, § 4-9.1(1) (2019). https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/boston/latest/boston_ma/0-0-0-17851

34 7 CFR § 210.20(g)(1) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2024-04-25/pdf/2024-08098.pdf

35 Id.

36 Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, 7 USC §8701, Sec. 4302. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-110publ246/pdf/PLAW-110publ246.pdf