Measuring Progress: Common Terms and their Limitations

Making progress towards food justice, food sovereignty, and the end of food apartheid relies on understanding and considering multiple indicators, such as food insecurity, hunger, food swamps, and food deserts. These indicators help identify areas of inequity, target action and investment, and track progress toward food access that is equitable and just. The following sections describe how these terms are used in food policy and research, as well as their limitations.

In this section:

Food Security

“Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

– United Nations’ Committee on World Food Security

“Food security includes the dimensions of 1) Availability (having sufficient quantities of food available on a consistent basis); 2) Access (having sufficient resources to obtain appropriate foods for a nutritious diet); 3) Use (appropriate use based on knowledge of basic nutrition and care, as well as adequate water and sanitation); and 4) Stability of these three dimensions.”

Food security is a desired outcome and progress indicator for food justice advocates. Definitions of food security may differ, but they generally share these elements: consistent access to food that is affordable, nutritious, and meets cultural and dietary preferences. Food security can also be described by the issues it solves, including food instability, obstacles to accessing food, hunger, and malnutrition. Communities may conceptualize and define food security differently. For example, the right to hunt, gather, and fish may be a necessary component of food security for Indigenous communities.

At the federal level, the USDA defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.” The USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) provides a validated survey tool for researchers to measure the household level of food security on a spectrum from high food security to very low food security. The USDA uses the classifications “high food security” and “marginal food security” to describe different levels of food security. The high food security classification means there are no indicators of food access issues. Marginal food security refers to the presence of food access issues, such as anxiety about food sufficiency or a food shortage within the household.

The USDA defines food insecurity as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” and distinguishes between low food security and very low food security. Low food security means there are indicators of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of food in the diet. Very low food security means that there are disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake in the household.

However, the term food security can be limiting when positioned as an ultimate goal, rather than one of many desired outcomes, because it does not adequately address the nutritional or diet quality of available foods or the root cause structural issues that create inequities and food insecurity in the first place. While food security is a helpful indicator of progress towards a more equitable food system, it is merely one step towards food justice, food sovereignty, and an end to food apartheid.

- Related Term: NUTRITION SECURITY

- Related Term: COMMUNITY FOOD SECURITY

- Related Term: FOOD ACCESS

- Related Term: FOOD SYSTEM RESILIENCE

Food Security Policy Examples

Detroit, Michigan’s Food Security Policy, drafted by the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, identifies eight areas for improving food security in Detroit, including: 1) access to quality food; 2) hunger and malnutrition; 3) impacts/effects of an inadequate diet; 4) citizen education/food literacy; 5) economic injustice within the food system; 6) urban agriculture; 7) the role of schools and other public institutions; and 8) emergency response.

Dacono, Colorado exempts certain purchases of food made with federal nutrition program assistance benefits or funds from the city sales tax on food.

Federal Way, Washington allows urban agriculture, such as community gardens and urban farms, as a permitted use in any zone throughout the city, and lists “increasing local food security” as part of the purpose of the policy.

San Francisco, California’s Healthy Food Retailer Incentives Program offers grants, technical assistance, and other incentives to “healthy food retailers” meeting specified requirements to increase access to healthy food in underserved areas.

Learn More about Food Security

- “Reach” by Lucie Cooper and Ava Davis: a mural series in Jackson, Mississippi depicting inequities in the ease/difficulty for people and communities in accessing healthy food

- “Household Food Security in the United States in 2020”: an annual report produced by the USDA Economic Research Service that covers household food security, food expenditures, and use of federal nutrition assistance programs

- “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World”: an annual report produced by United Nations agencies to monitor international progress towards food security

- “Food Systems Resilience: Concepts & Policy Approaches” by Jenileigh Harris & Emily Spiegel, Center for Agriculture and Food Systems at Vermont Law School

Food Desert

The term “food desert” has been used by local, state, and federal governments, including the USDA, to describe areas with low access to grocery stores. The USDA Economic Research Service initially analyzed 2000 and 2006 census data on locations of supermarkets, supercenters, and large grocery stores to identify the first “food deserts” in the US. The Food Access Research Atlas(formerly called the Food Desert Locator) is a mapping tool that visualizes more recent data from 2019.

After identifying food deserts as areas marked by low access to grocery stores, the US government launched the Healthy Food Financing Initiative5 (HFFI) as a coordinated federal program to increase healthy food access and eliminate food deserts by providing grant funding and technical assistance to eligible fresh, healthy food retailers and enterprises in low-income communities. In 2019 and 2020 alone, the HFFI awarded $4.4 million in targeted grants to 30 projects designed to improve access to fresh, healthy food through food retail.

However, the term food desert is being phased out at the federal level, including in the HFFI. The USDA now refers to food deserts as “low-income and low-access areas” in their Food Access Research Atlas. Given that the term food desert has been in use by the federal government since at least 2008,6 it is still commonly found in policy language, grant applications, and market research among grocery store companies. For example, the New Jersey Food Desert Relief Program uses the term to identify priority areas eligible for certain funding.

Although the term food desert highlights the spatial relationship between people and grocery stores, it is problematic and has been critiqued for several reasons. Food desert has a negative connotation, implying that neighborhoods with low access to healthy food are barren and desolate landscapes. The term also suggests that the problem of low access to healthy food is naturally occurring meaning that the solution is simply to increase healthy food retail options, such as grocery stores, healthy corner stores, and farmers’ market programs. It also does not acknowledge that people are willing to travel to get quality, affordable food, including households with low incomes.

The term food desert is rooted in deficit. As such, it does not accurately reflect the vibrancy of communities experiencing low access to healthy food. Moreover, by implying that scarcity of healthy food is a natural phenomenon, it masks the deliberate policy decisions that have created this scarcity. Finally, the term does not recognize the resulting racial disparities created by these policy decisions and how they disproportionately impact people of color. Consequently, it does not emphasize the need for systemic solutions.

Lasty, to create effective systemic and policy solutions to increase healthy food access, it is important to understand why food deserts may exist in the first place and their root causes. In rural areas, food deserts may exist for various reasons such as rural communities losing their small and independent grocers as bigger supercenters and large retailers offer more affordable food options, though they may be located farther away. In urban areas, post-World War II suburbanization patterns shaped the food system, with many supermarkets relocating from inner-city neighborhoods with low incomes to white suburbs, leaving these areas with limited access to grocery stores.7 The Federal Housing Administration’s Home Owners Loan Corporation developed maps that ranked residential neighborhoods with grades “A” through “D” based on the highest (“A”) to the lowest (“D”) ratings, with “D” areas marked in red on the maps.8 This practice known as redlining led to spatially organized and distributed poverty based on race, which led major food retailers to leave these neighborhoods because they supposedly had higher operating expenses and lower profit margins.9

Food Desert Policy Examples

There are many examples of the term “food desert” used in laws and programs that seek to facilitate greater access to healthy food.10 However, because this term is now considered by many to be problematic, we are providing one example of a city that has shifted away from using this term to use alternatives such as “healthy food priority areas”:

- Baltimore, Maryland has shifted away from using the term food desert and now refers to these areas as Healthy Food Priority Areas. Elsewhere, the city has previously defined “food desert incentive areas” in a law that provides a personal property tax credit for qualifying supermarkets.

Learn More about Food Deserts

- “Place Matters” by Clint Smith: a spoken word piece on low food access areas in Washington, DC

- Food Access Research Atlas: USDA’s Economic Research Service maintains an interactive map of supermarket availability in low income and low access areas within the United States

- “Critics say it’s time to stop using the term ‘food deserts’” by Lela Nargi

- “Beyond ‘food deserts’: American needs a new approach to mapping food insecurity” by Caroline George Adie Tomer

- “Defining Low-Income, Low-Access Food Areas (Food Deserts)” by the Congressional Research Service

Food Swamp

Food swamps are “areas in which large relative amounts of energy-dense snack foods, inundate healthy food options.”

– Donald Rose, J. Nicholas Bodor, Chris Swalm, Janet Rice, Thomas Farley & Paul Hutchinson, Deserts in New Orleans?: Illustrations of Urban Food Access and Implications for Policy

The term “food swamp” refers to an area with a high density of food retail outlets that tend to feature low cost, unhealthy foods, such as convenience stores, fast food establishments, and gas stations. The term highlights how the relative abundance of cheap fast food and junk food options may influence health more than access to outlets that sell healthier and more nutritious food. In fact, some research has shown that living in an area classified as a food swamp is a better predictor of adult obesity inequities than living in an area classified as a food desert.11 Research has also shown that food swamp environments are more common in neighborhoods with low incomes, and particularly impact Black communities.

As the term suggests, food swamps exist when there is an imbalance in the local food environment, where unhealthy food outlets outnumber those that sell healthy food, driving poor health. Like the term food desert, food swamp can be used as a measurement tool that considers healthy food access and the food environment. However, the term takes a different perspective by focusing on the food access challenges of those who are navigating a food environment filled with the types of unhealthy food outlets that show up when supermarkets and grocery stores are not present.

Some of the same forces mentioned in the previous section that created food deserts are also responsible for food swamps too, including historical redlining, white flight, transportation inequities, barriers to lending and entrepreneurship for local residents, concentrated poverty, and outdated zoning rules.11 These factors are important to understand and consider because interventions and policy solutions must consider the root causes in order to alleviate existing food swamps and prevent new swamps from emerging.

Communities aiming to alleviate food swamps can begin by organizing with neighbors and other community stakeholders to identify specific issues, express their needs, and discuss community-driven solutions. Putting pressure on business owners to increase healthy food offerings may be one approach. However, it is worth noting that organizing together with neighbors, elected officials, and other community stakeholders to collectively put pressure on food business owners will have a greater impact than any of those groups individually. Elected officials who are in positions of power and influence should use their capital to work with and empower the community (see Food Access Policy Change through Resident Engagement) in developing policy solutions.

Communities may also consider mapping neighborhood-level food store access to identify food swamps, which then can be prioritized for interventions that restrict or disincentivize retailers primarily selling unhealthy or high fat/sugar/salt foods through zoning, licensing, minimum stocking standards (like the Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance) and other local policies, especially those that would apply to new retailers. To achieve a more equitable and balanced neighborhood food environment, communities could simultaneously incentivize existing retailers to carry more fresh fruits and vegetables, which may require technical assistance and equipment to support these efforts.

Although the term seems to provide a better measurement tool than food desert, some critique use of the term food swamp as they do food desert, noting that it does not emphasize or adequately highlight the root causes of limited access to healthy food in these areas.12,13 Instead, they suggest that food apartheid may be a better descriptor because it highlights how structural and institutional racism led to the current food landscape that we see in these areas.

Food Swamp Policy Examples

Arden Hills, Minnesota requires that any fast-food restaurant be located at least one-quarter mile from another fast food establishment, and at least 400 feet from schools, churches, public recreation areas, and residentially zoned property.

Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Healthy Neighborhood Overlay District establishes dispersal requirements of one mile between small box discount stores (such as dollar stores), exempting stores that use at least 500 square feet for the sale of fresh produce. Read this article to learn more.

Calistoga, California prohibits drive-thru windows at food service establishments and bans fast food, or “formula” restaurants to protect the “small-town” character.

South Los Angeles created a one-year moratorium on permits for new fast food restaurants. However, it is worth noting that this policy has been critiqued because it has not produced the intended results and has not reduced obesity in the city.

Prince George’s County’s Food Equity Council has pursued multiple policy approaches to address inequities in the food system associated with food swamps. “Food Access and Equity in Prince George’s County” includes a map of fast food establishments and other restaurants (see page 17) and identifies healthy food access priority areas.

Learn More about Food Swamps

- Fertile Ground: a documentary discussing food swamps, food insecurity, and community resilience in Jackson, Mississippi.

- “Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better Than Food Deserts in the United States” by Kristen Cooksey-Stowers, Marlene Schwartz & Kelly Brownell.

- “How Latina Mothers Navigate a ‘Food Swamp’ to Feed their Children: a Photovoice Approach” by Uriyoán Colón-Ramos, Rafael Monge-Rojas, Elena Cremm, Ivonne Rivera, Elizabeth Andrade & Mark Edberg

- “Racial Differences in Perceived Food Swamp and Food Desert Exposure and Disparities in Self-Reported Dietary Habits” by Kristen Cooksey-Stowers, Qianxia Jiang, Abiodun Atoloye, Sean Lucan & Kim Gans

- The City Planner’s Guide to the Obesity Epidemic: Zoning and Fast Food by Julie Samia Mair, Matthew Pierce, and Stephen Teret

- Informational and Behavorial Cues in the Food Environment and Their Effect on Diet Behavior – Developing a Valid and Reliable Food Swamp Environments Audit (FS-EAT) Tool: Spatial Patterns and Implications for Land Use Zoning Policies by Kristen Cooksey-Stowers et al.

- “U.S. county “food swamp” severity and hospitalization rates among adults with diabetes: A nonlinear relationship” by Aryn Z. Phillips & Hector P. Rodriguez

- Relationships between Vacant Homes and Food Swamps: A Longitudinal Study of an Urban Food Environment by Yeeli Miu et al.

Hunger

Hunger is “an uncomfortable or painful physical sensation caused by insufficient consumption of dietary energy. It becomes chronic when the person does not consume a sufficient amount of calories (dietary energy) on a regular basis to lead a normal, active and healthy life.”

– Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Hunger is “a potential consequence of food insecurity that, because of prolonged, involuntary lack of food, results in discomfort, illness, weakness, or pain that goes beyond the usual uneasy sensation.”

– Committee on National Statistics of the National Academies

Hunger is a general term used to describe the condition when a person does not consume enough food to meet their body’s nutritional needs. It is often used interchangeably with the terms “undernourishment” and “malnutrition” to describe a potential consequence of food insecurity. Hunger can cause a wide range of health and developmental consequences, particularly for children, if experienced for a prolonged period.

Hunger occurs at the individual level, which makes it more difficult to assess compared to household-level indicators like food insecurity. This is why many national surveys and health targets (such as Healthy People 2030) have used food insecurity as a proxy for assessing hunger. In some instances, the term hunger has been used to describe data that in fact measured food insecurity. Hunger is a simpler term, which may be why it is more commonly used in public opinion polling. However, the conflating of hunger and food insecurity has drawn criticism, including from the Committee on National Statistics, which recommended that USDA stop using the term hunger to describe food insecurity indicators.

Hunger Policy Examples

Many localities designated food banks and other entities providing food to economically disadvantaged individuals as “essential businesses” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Schools were also typically exempt from stay-at-home orders during the pandemic and leveraged new regulatory flexibility in USDA’s School Meal programs to address hunger and food insecurity in their communities. Visit the Healthy Food Policy Project’s Municipal COVID-19 Food Access Policies database for policy examples.

Prince George’s County, Maryland, created a program to help farmers’ markets acquire and use the technology needed to process benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Learn More about Hunger

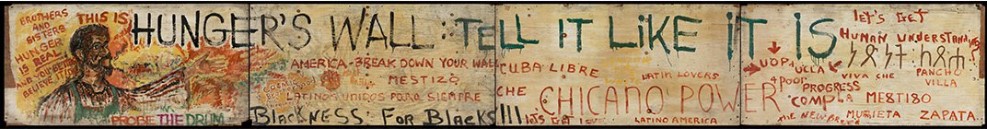

- Hunger’s Wall: Tell It Like It Is: a mural created during the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968 in Resurrection City on the National Mall; now housed at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC

- Hunger Through My Lens: a multimedia advocacy platform organized by Hunger Free Colorado for Coloradans experiencing hunger to share their stories through photography, writing, and voice recordings

- Witnesses to Hunger: a program organized by the Center for Hunger-Free Communities at Drexel University that facilitates policy advocacy by people who are affected by hunger, including participants from Washington, DC, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Connecticut

- “Hunger and Poverty in America” by Food Research Action Center (FRAC)

- “Hunger and food insecurity are not the same. Here’s why that matters – and what they mean” by Simran Sethi

Discussion Questions

- What terms or ideas best reflect or describe your experience with improving local food systems? What resonates with you, and why?

- What terms do you find confusing or problematic, and why?

- How do the equity frameworks of food justice, food sovereignty, and food apartheid make you think differently about the food system and policy solutions? How do the common terms and indicators such as food insecurity, hunger, food swamps, and food deserts make you think differently about the food system and policy solutions?

Next: Conclusion

4Caspi, C. E., Sorensen, G., Subramanian, S. V., & Kawachi, I. (2012). The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health & place, 18(5), 1172-1187.

5HFFI is a public-private partnership administered by the Reinvestment Fund on behalf of USDA Rural Development was established by the 2014 Farm Bill and reauthorized in 2018 to improve access to healthy food in underserved areas. Only projects located in Low Income, Low Access census tracts (formerly called “Food Deserts”) are eligible for HFFI funding. For more information see here: https://www.investinginfood.com/about-hffi/

6P.L. 110-246, Title VI, §7527.

7Joyner, L., Yagüe, B., Cachelin, A., & Rose, J. (2022). Farms and gardens everywhere but not a bite to eat? A critical geographic approach to food apartheid in Salt Lake City. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 11(2), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2022.112.013

8Rhodes, Jason. “Geographies of Privilege and Exclusion: The 1938 Home Owners Loan Corporation “Residential Security Map” of Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. September 07, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170907. See “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America” https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58

9Joyner, L., Yagüe, B., Cachelin, A., & Rose, J. (2022). Farms and gardens everywhere but not a bite to eat? A critical geographic approach to food apartheid in Salt Lake City. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 11(2), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2022.112.013

10See the Healthy Food Policy Project Policy Database for examples: https://healthyfoodpolicyproject.org/policy-database?_policies_search=food%20desert

11Cooksey-Stowers, K., Schwartz, M. B., & Brownell, K. D. (2017, November 14). Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better Than Food Deserts in the United States. PubMed Central. Retrieved June 14, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5708005/.

12Johnson, B. (2022, April 21). U study in north Minneapolis asks: Do we eat more fast food because we want it or because it’s there? StarTribune. https://www.startribune.com/do-we-eat-more-fast-food-because-we-want-it-or-because-its-there-u-study-asks-in-north-minneapolis/600166722/

13Agyeman, J. (2021, March 9). How urban planning and housing policy helped create ‘food apartheid’ in US cities. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-urban-planning-and-housing-policy-helped-create-food-apartheid-in-us-cities-154433

14Sevilla, N. (2021, April 2). Food Apartheid: Racialized Access to Healthy Affordable Food. Natural Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/experts/nina-sevilla/food-apartheid-racialized-access-healthy-affordable-food